Oak Park, CA 91377

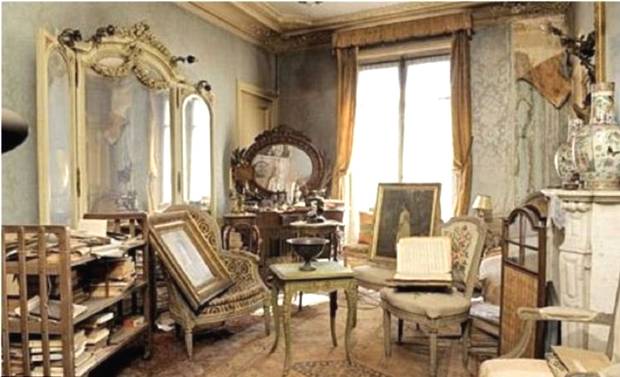

There is a nice mixture of furniture, artwork, collectables and household items. It features a collection of Tengra porcelain figurines many that are large and rare!

The furniture includes the following:

English Dark wood style dining table with 6 dining chairs and buffett. King size bed with brass headboard, Queen size bed with brass headboard, full size bed, antique German tea cart, very cool 60’s vintage Lucite screen, small dressers, lamps, chairs and quality patio furniture, etc.

Artwork includes a lithographic work by Roy Lichtenstein, Christian art, 50’s mid-century art, Nasa art, Chinese scrolls and an antique Italian oil painting.

There are men’s and woman’s clothing and costume jewelry, cameras and electronics, etc.

There are a lot of newer kitchen items, pot and pans, cutlary, small appliances, microwave, crystal, vintage dish set, newer Kenmore refrigerator, bedding, towles and sheets, children’s toys, books and Bibles and Christmas decorations, tools in a full garage. Too much to list.

Address:

Conifer Street

Oak Park, CA 91377

Times:

Sat, June 27 – 8:30am – 5:00pm

Sun, June 28 – 9:00am – 4:00pm